Affordable Mass and the New Reality of Deterrence

War games show the U.S. would exhaust its missile stocks in days

Affordable Mass and the New Reality of Deterrence

Recent analyses of U.S. war‑games and stockpiles paint a grim picture for a cross‑strait war. In one study the Center for Strategic and International Studies concluded that the United States would likely run out of some munitions—such as long‑range precision‑guided weapons—in less than one week in a Taiwan Strait conflict CSIS report. A separate simulation run by the House Select Committee on China found that America’s cache of long‑range anti‑ship missiles would be spent within three to seven days, and that long‑range cruise missiles would be gone within a month John Locke Foundation. Even if Taipei manages to buy hundreds of Javelin anti‑tank missiles and other munitions, the United States does not have the industrial capacity to replace them at the pace a high‑intensity war would consume them.

Quantity, then, matters. Affordable, capable munitions built for scale are at least as important as exquisite platforms. Massed, ready‑to‑fire weapons alter an adversary’s calculus more than promises of future deliveries. And to avoid fragile trans‑Pacific logistics, those munitions must be manufacturable near or in the theatre. That reality has profound implications for U.S. strategy and for how Taiwan and other front‑line states plan their defences.

The Empty Bins Problem

War‑game results underscore how quickly America’s magazine would empty. In one simulation, U.S. forces expended more than five thousand long‑range missiles in just three weeks; within the first week they exhausted stocks of long‑range anti‑ship missiles, and replacing those weapons would take roughly two years Yahoo News. These findings echo the CSIS report’s warning that the U.S. industrial base lacks the surge capacity needed for protracted conflict CSIS report. Put bluntly, America cannot build its way out of a fight once the shooting starts.

Delivery is another problem. With China likely to blockade Taiwan, getting weapons across the Pacific after hostilities break out would be nearly impossible. That’s why analysts recommend stockpiling—and even producing—munitions in or near the theatre. Yet the backlog of weapons Taiwan has already purchased from the United States shows how far reality lags behind rhetoric. As of late 2023, Washington owed Taipei about $19 billion in foreign military sales Reuters. Some of these systems were ordered as early as 2017; analysts note that the backlog stems not from aid to Ukraine but from limitations in the U.S. defence industrial base and inefficiencies in the arms‑sales process Cato Institute. Slowing aid to Ukraine will not fix Taiwan’s queue because the bottleneck is structural.

Production Diplomacy and Friend‑Shoring

If the United States cannot build enough weapons at home fast enough, then what? The Pentagon’s National Defense Industrial Strategy offers one answer: production‑oriented diplomacy. The strategy calls for creating resilient supply chains and leveraging “friend‑shoring”—outsourcing production of critical defence materials and munitions to trusted allies such as Japan and Australia—to reduce reliance on unstable or adversarial suppliers K&L Gates. It envisions networked production chains among allies to expand capacity and resilience, and proposes convening Indo‑Pacific partners to collaborate on manufacturing challenges before a crisis hits K&L Gates. One early example: the United States is negotiating with Japan to use Japanese shipyards for U.S. Navy overhauls so warships can remain forward‑deployed in Asia K&L Gates.

This approach—call it production diplomacy—reframes alliances as integrated manufacturing networks. By designing systems at home but building them abroad, Washington could tap the industrial capacity of its partners. Modular, open architectures and digital engineering would allow designs to be shared securely and updated rapidly. Once a weapon is proven, the United States could license its intellectual property to allied manufacturers under strict end‑use monitoring. Partners would assemble drones, anti‑ship missiles and loitering munitions in their own facilities, stockpiling them locally. No single country would need to supply every component; a networked supply chain would buffer the alliance against blockades and shocks.

Toward an Irregular Architecture

These ideas point to an irregular defence architecture that abandons the assumption that all weapons must be built in the United States. The core components:

- Design at home, build abroad. American universities, national labs and defence start‑ups remain the creative hub, but production occurs in allied factories with secure data‑sharing protocols.

- Franchise the production. Once a system is proven, license its intellectual property to trusted manufacturers overseas under strict export controls and end‑use monitoring.

- Local stockpiles deter aggression. Weapons built and stored in places like Taiwan, Japan or Australia can be surged quickly in a crisis. Massed, affordable munitions near the front deter by presenting an adversary with a ready arsenal rather than a promise of future shipments.

- Networked supply chains. Friend‑shoring encourages allied nations to specialise and share components, buffering the system against blockades and supply shocks K&L Gates.

Such a model would relieve pressure on the U.S. industrial base and chip away at Taiwan’s backlog. It aligns with the National Defense Industrial Strategy’s call for production‑oriented diplomacy and the emerging alliance‑centric defence posture. But it carries risks. Intellectual‑property security is paramount; franchise agreements must include cyber protections and end‑use monitoring. Export‑control laws will need reform to allow co‑production while safeguarding sensitive technologies. Partner nations must have reliable political systems and manufacturing capabilities. There is also the danger of escalation: Beijing may view arms factories in Taiwan or Japan as provocative.

Building the Arsenal of Democracy

For decades, America’s arsenal has relied on a sprawling but highly centralised industrial base. That model may not be nimble enough for the multipolar world now taking shape. The war‑game results from CSIS and the House China committee show that the United States would exhaust its missile stocks almost immediately CSIS report. The roughly $19 billion backlog in Taiwan’s weapons orders Reuters and the documented bottlenecks in the foreign‑military‑sales process Cato Institute underscore that the status quo is untenable. The nascent shift toward production diplomacy and friend‑shoring suggests Washington understands the problem. What’s still missing is a more radical vision: a franchised defence architecture that decentralises production while preserving American innovation. It’s an irregular mission for irregular times. Without it, the free world may find itself facing a formidable foe with an empty magazine and a backlog of regrets.

Irregular Warfare and the Gray Zone

As the global balance of power becomes multipolar, adversaries are increasingly operating below the threshold of open war. The U.S. Army’s Irregular Warfare manual explains that irregular warfare complements conventional operations by leveraging non‑military power sources and enables partners and proxies to create and exploit strategic advantages without escalating to full‑scale war. It defines irregular warfare as a form of warfare where state and non‑state actors campaign through indirect, non‑attributable activities and emphasizes that these campaigns may involve enabling partners, proxies, or surrogates to achieve shared objectives.

Strategic competition literature describes this space between peace and war as the “gray zone.” Revisionist state and non‑state actors—including Russia, China, Iran, North Korea, and violent extremist organizations—are evading U.S. strength by competing below the threshold of a coercive military response. Operating in this gray zone allows them to contest international rules and norms without triggering a conventional response. These “gray‑zone” activities include irregular warfare, low‑intensity conflict, and gradual operations that blur the line between cooperation, competition, and armed conflict.

Designing an “irregular architecture” for this kind of war without war means pre‑positioning the tools of influence and resistance. Local and regional depots stocked with loitering munitions, anti‑armor weapons, small drones, and information‑operations kits would give aligned forces the means to fight oppression and preserve democracy long before a conventional war begins. The same franchised production model we propose for high‑end munitions—designed in the United States and built abroad under license—should extend to these irregular kits. By empowering partners and proxies to contest adversaries in the gray zone, we make a resilient network that can thrive even when America is stretched across multiple fronts.

Data and the Growing Gray Zone

As the Great Game resumes after a long pause following the trauma of World War II, skirmishes and proxy conflicts short of open war—known in Pentagon jargon as “outside declared theatre of active armed conflict” (ODTAAC)—will sprout up with increasing frequency. In a multipolar world, the United States, NATO, and the United Nations are no longer the sole arbiters of what constitutes a “declared theatre of active armed conflict” (DTAAC). Under the laws of armed conflict, certain obligations apply only once a theatre is declared; below that threshold, an ambiguous “conflict short of armed conflict” or low‑intensity conflict unfolds with fewer constraints. ODTAAC environments often mature into declared theatres as escalation occurs.

To understand and anticipate these grey‑zone confrontations, analysts need robust data—several projects offer valuable quantitative inputs. The UCDP’s Managing Intrastate Low‑Intensity Conflict (MILC) dataset compiles third‑party interventions in low‑intensity intrastate conflicts from 1993–2004, recording the date of each intervention, the interveners, and the type of measure. ACLED’s Conflict Index and its broader event dataset provide near‑real‑time data on political violence worldwide, measuring conflicts across indicators such as deadliness, danger to civilians, geographic diffusion, and the number of armed groups, and they include the location, date, actors, and fatalities of each event. Macro‑level indices like the Fund for Peace’s Fragile States Index, which assesses the vulnerability of states to collapse, add important economic and governance context.

These datasets can help map where low‑intensity conflict and ODTAAC operations are occurring and which are likely to evolve into declared theatres. The Pentagon’s civilian casualty reports and related debates underscore that there is no single arbiter of what constitutes a declared theatre. There is little transparency about lethal strikes outside those areas. As regional powers assert themselves, grey‑zone skirmishes and proxy fights will multiply, and today’s ODTAAC environments can quickly mature into declared theatres.

That reality reinforces the need for an irregular defence architecture. A data‑driven understanding of where grey‑zone conflicts are brewing allows the United States and its allies to pre‑position the tools of influence and resistance. Local and regional depots stocked with loitering munitions, anti‑armour weapons, drones, communications kits, and information‑operations tools can give aligned forces the means to contest oppression and preserve democracy before clashes spiral into full‑scale war. The franchised production model—designing in the United States and building abroad under licence—ensures this irregular kit is available where and when needed.

The constraint isn't where there is instability—there's a community of interest in the world between SOF and CIA alumni, a human network that reinforces and anticipates zones of pre-conquest.

Manufacturing at Home and Abroad

Onshoring U.S. supply chains is a popular political instinct. Yet Deloitte notes that some supply chains cannot be fully reshored: key resources exist only in certain places, and replicating networks at home can cost more than the global industry’s value. The consultancy says “friend ‑shoring” — developing networks of trusted suppliers among allies — should complement, not replace, onshoring. Friend ‑shoring can improve resilience while maintaining economic growth.

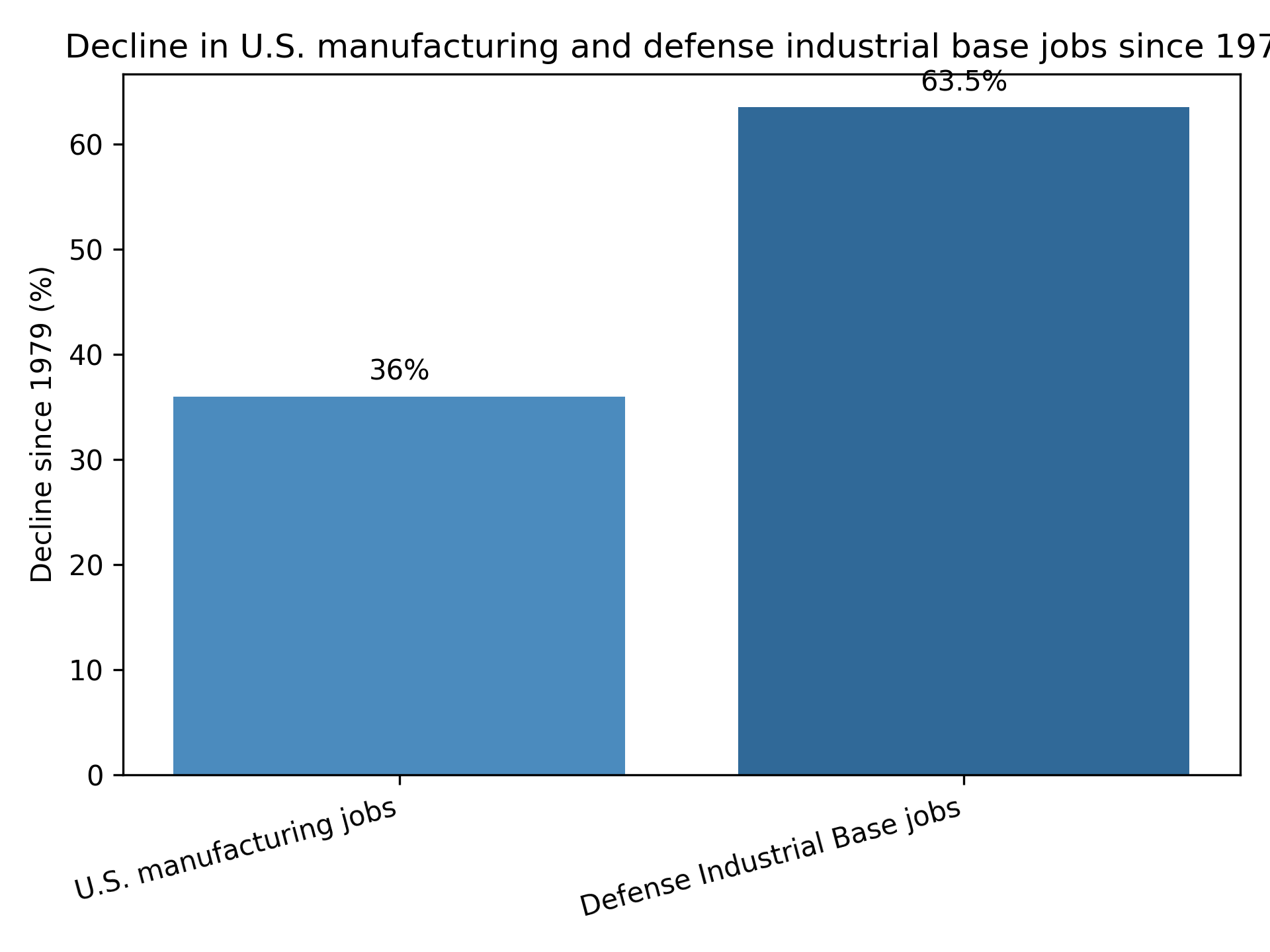

Friend ‑shoring is already emerging as an industrial strategy. Agreements like AUKUS and the ICE Pact leverage the industrial capacity of allies, reduce inefficiencies and create economies of scale. Over the past four decades, U.S. manufacturing jobs have shrunk by about 36 percent and defence industrial base jobs by 63.5 percent. Friend ‑shoring can secure guaranteed orders and help rebuild manufacturing capacity while the United States invests in on ‑shoring. But critics warn that friend ‑shoring could politicise trade and exclude developing countries, and it may add inflationary pressure. To mitigate these risks, friend ‑shoring should be confined to sectors linked to national security.

A way to balance resilience and development is “frontier ‑shoring.” Under this model, the United States designs systems at home, licenses the intellectual property to trusted partners in frontline or developing economies, and helps them build local depots. These frontier franchises take friend ‑shoring one step further by moving production even closer to the theatre. Coupled with renewed on ‑shoring, frontier ‑shoring ensures that if war breaks out, there is always capacity — whether in America, an ally or a frontier partner — to produce the munitions and irregular warfare kits needed for the next gray ‑zone fight.

To visualise the industrial decline and the urgency of friend ‑shoring and frontier franchises, the chart below compares the decline in U.S. manufacturing employment with the much steeper drop in defence industrial base jobs.

The United States would run out of many key munitions within days in a major conflict. Irregular warfare and gray-zone conflicts will proliferate as great-power competition resumes. Friend-shoring and frontier-shoring can supplement on-shoring by allowing trusted partners to build U.S.-designed systems while the domestic industrial base is rebuilt.

Stay tuned (offset work-in-progress)

Open-source datasets like UCDP’s low-intensity conflict data, ACLED’s Conflict Index, and the Fragile States Index can help anticipate where low-intensity conflicts may emerge.

• UCDP's Managing Intrastate Low‑Intensity Conflict dataset: event‑level data on third‑party interventions, dates, interveners, and measures.

• ACLED Conflict Index: near‑real‑time data on political violence worldwide, including location, date, actors, fatalities, and indicators like deadliness and danger to civilians.

• Fragile States Index: macro-level assessment of state fragility, highlighting economic and governance pressures that can lead to collapse.

Policy Considerations to better by, with, through

- Establish a multinational working group on frontier‑shoring. Bring together allies and trusted partners to identify suitable frontier manufacturing locations, share best practices, and coordinate licensing of U.S. designs.

- Forge data‑sharing partnerships for ODTAAC analysis. Regularly share datasets like UCDP, ACLED, and the Fragile States Index across allied intelligence and academic communities to anticipate emerging gray‑zone conflicts.

- Create incentives for U.S. firms to license IP abroad. Use tax breaks, investment credits, or defence procurement clauses to encourage U.S. companies to franchise their designs to allied producers while maintaining strict export controls.

- Support frontier economies with training and infrastructure. Provide technical assistance and financing to help partners build the industrial and logistical capacity required for frontier‑shoring, ensuring quality control and security. Governance pressures that can lead to collapse.